MAD MEN AT FRIEZE ART FAIR

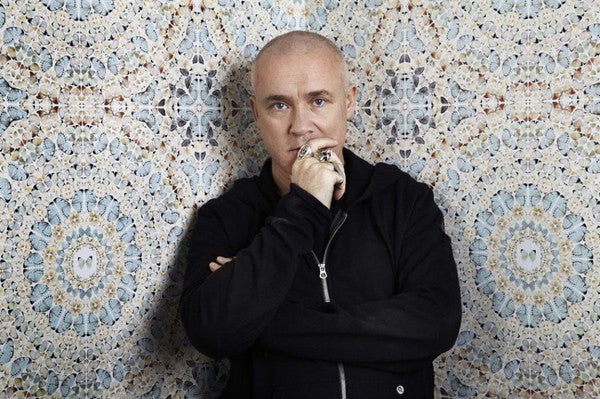

Is Damien Hirst Don Draper in disguise?

by KOD Staff

What do Don Draper and Damien Hirst have in common? The similarities between TV series Mad Men’s lead character and the world’s highest earning artist reveal how art is becoming more about branding, especially in the context of Frieze Week London, one of the world’s most recognized art fairs. Of course artists will always be at the mercy of money, but is art just an exercise in personal branding?

Both Hirst and Draper manipulate branding to their advantage. As Creative Director of advertising firm Sterling Cooper, Draper – played by Jon Hamm – is responsible for creating corporate identities, but he is also a brand in his own right. On screen he is a marketing genius, preying on America’s insecurities to create glittering advertising campaigns. At the end of each episode, he inspires a multitude of idolizing blogs and online discussions.

Matthew Weiner, writer of Mad Men, has created an icon – no easy feat in today’s society, endemic with cynicism. But Draper’s branding endears us to old-school masculinity: he’s always in a suit, drinking in his office and sleeping with his secretaries.

Hirst told The Independent, “Becoming a brand name is a really important part of life.” And with an over-riding theme of pop mortality, his work is consistent and therefore immediately recognizable. His brand is world famous, justifying his sky high prices. As a student he was proactive, putting on events and mercilessly networking.

Thanks to his corporate mentality, in the past Hirst has been compared to the late Thomas Kinkade. Kinkade was a mass market artist, specializing in a tacky Christmas card aesthetic, set against a backdrop of devout Christianity. He produced prints of his works in bulk, selling them on the QVC shopping network. He was widely criticized for the commercialization of his art yet his sales reached nearly $100 million annually.

It was Kinkade’s everyman appeal that made him successful and he estimated that one in twenty American homeowners had a copy of one of his paintings. In an interview with Time Out in 2009, Hirst expressed Kinkade-esque aspirations - 'I always feel a bit trapped when a painting goes for millions and only one person can have it. If you can have that as well as a poster on every student's wall, then you're in a very enviable position.'

At fairs, like Frieze, the marketplace manifests itself under one noisy roof so work needs to scream out brand identity to be heard above the rabble.

Today, this hybrid of artist-meets-businessman is necessary thanks to a globalized art market and the internet. Collecting art is now an international hobby and so, for artists, there’s more competition and a greater need to stand out. At fairs, like Frieze, the marketplace manifests itself under one noisy roof so work needs to scream out brand identity to be heard above the rabble.

“Advertising is based on one thing: happiness,” Draper tells the boardroom in season one. “Happiness is freedom from fear. It's a billboard on the side of a road that screams reassurance.” Mad Men shows us the way advertising toys with human emotion. In the hands of Draper, products promise a better life. For Lucky Strike, the cigarette company, he created the slogan, ‘It’s Toasted’. Conjuring warm and wholesome images, the words said – don’t worry about science, it’s still okay to smoke.

Hirst uses similar techniques to appeal to his audience. His sculptures feature animal carcasses, pickled and perfectly preserved in formaldehyde solution – the subject matter is morbid but the appearance is serene.

Like the floating farm animals, his butterfly paintings are reassuring because they’re beautiful. These works separate death from its dark and rotting image, gently comforting their audience: maybe dying isn’t that bad. However, this kind of reassurance isn’t cheap. Hirst’s sale at Sotheby’s in 2008 raised £111 million.

But in Mad Men’s season six, Draper reveals that some things are too precious to be prodded and polished by advertising. In a meeting with Hershey, the chocolate company, he describes growing up in a brothel, remembering how Hershey bars were the only thing that made him feel like a normal kid. “If I had my way, you would never advertise,” he tells them. “You shouldn’t have someone like me telling that boy what a Hershey bar is. He already knows.”

Draper cherishes the way Hershey’s brand identity has grown organically, believing that a manufactured message would undermine its audience. Yet Hirst manages his brand ruthlessly. This week the artist descends on Qatar with a triple pronged attack – he collaborates with Prada in the Qatari desert; he opens his largest ever exhibition in Doha and he recently unveiled fourteen fetus sculptures.

Both Draper and Hirst sell ideas in the form of products, so the artist and the ad man are not so different. But like Draper, Hirst should know his limit – when branding is necessary and art is sacred.