DUCHAMP: THE END OF ART HISTORY?

Can artists ever progress further than the father of Conceptualism?

by Peter Yeung

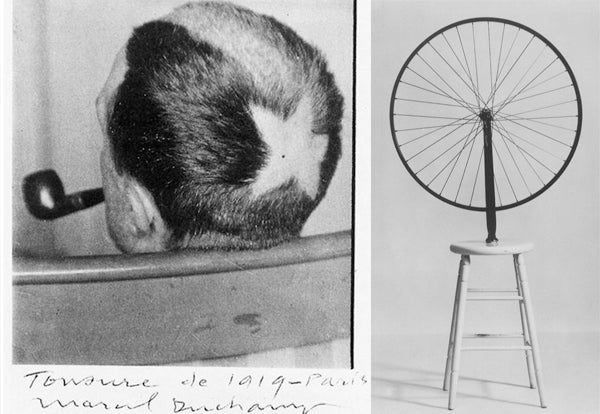

In 1913, an artist from the tiny municipality of Blainville-Crevon in the north-west of France mounted a bicycle wheel on a painted wooden stool, and changed the art world forever. The 25 year old Marcel Duchamp, the fourth of seven children, had created the first of what he would later term “readymades” – art made from prefabricated materials – and by doing so, critically undermined the hitherto artistic hierarchy. No longer was artisanship a necessity in art: Conceptualism was born.

Right: In 1919, Duchamp had a comet shape shaved into his hair, a gesture pre-empting the body art movement of the later 20th century. Left: Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel - 1913

While Duchamp was initially associated with movements such Cubism, Dadaism, Fauvism, and Surrealism, he soon came to reject "retinal" art, which – he contended – only existed to please the eye. Duchamp wanted to get rid of beauty and craft, in favour of work that stimulated the mind. It was perhaps the most important artistic gesture made since he advocated it over a century ago, and remains impossible to ignore in contemporary discourse. As American artist Joseph Kosuth puts it: "All art (after Duchamp) is conceptual (in nature) because art only exists conceptually.”

Left: Nude Descending a Staircase no.2 - 1912. Right: Marcel Duchamp emanates his famous painting in LIFE Magazine

But much in the way that political scientist Francis Fukuyama famously decried the “end of history” in 1992, has Marcel Duchamp’s oeuvre resulted in the end of art history? Is it possible to progress beyond his all-enveloping theory? Duchamp’s penchant for chess would suggest a familiarity with endgame, and it’s unfeasible to imagine any young Western artist these days not being influenced by Duchamp, consciously or not. The radical implications of Conceptualism – that anything can be art and that an artist need not have physically constructed a work to have created it – are why it remains so fertile, and undoubtedly, controversial nowadays.

![Marcel Duchamp, Paysage fautif [Faulty Landscape]-1946. Seminal fluid on Astralon, backed with black satin.](http://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0200/7124/files/marcel_duchamp-600-seminal_fluid-body_art-semen-Kids_of_Dada_grande.jpg?48294)

Marcel Duchamp, Paysage fautif [Faulty Landscape]-1946. Seminal fluid on Astralon, backed with black satin.

A consideration of the calibre and diversity of the artists influenced by Duchamp make it somewhat easier to comprehend why his theories are so entrenched. Jasper Johns, Jackson Pollock, Robert Rauschenberg, Shaun Gladwell, Mona Hatoum, Richard Hamilton, and Sir Peter Blake are just a few of the 20th century figures to have clearly been impacted. An exhibition at London’s Barbican in 2013, meanwhile, argued for Duchamp’s influence on people as diverse as composer John Cage and choreographer Merce Cunningham. Whereas, Andy Warhol was so taken by the Frenchman that he made several short films of Duchamp and in the 1960s, even hatched a failed plan to make a 24 hour film about him.

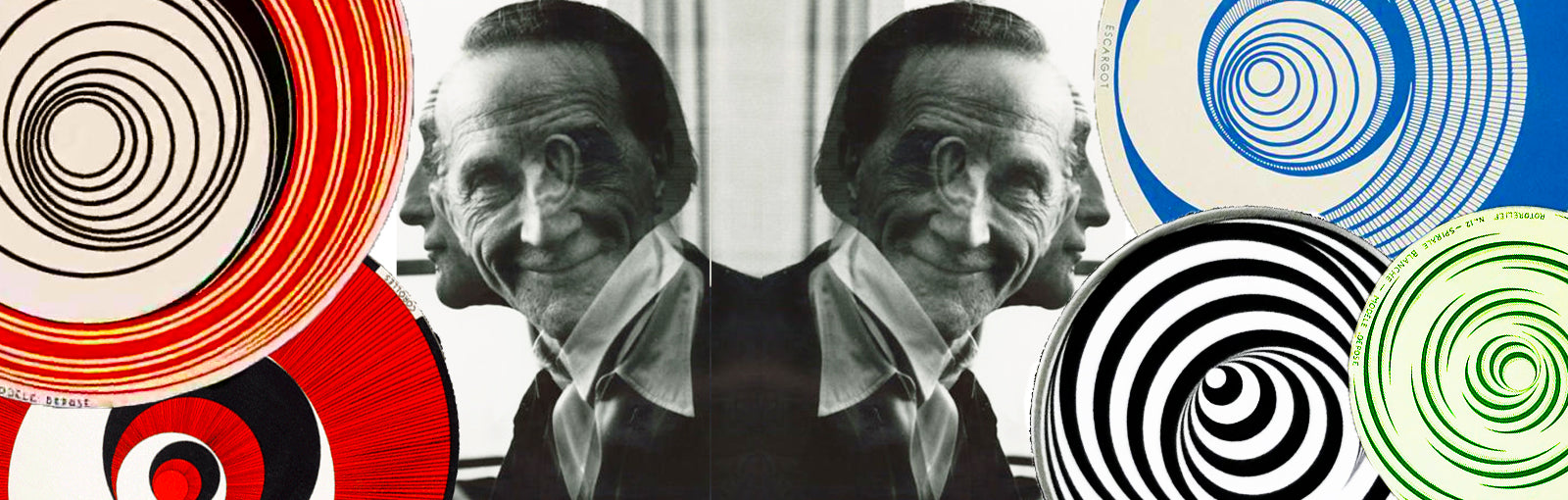

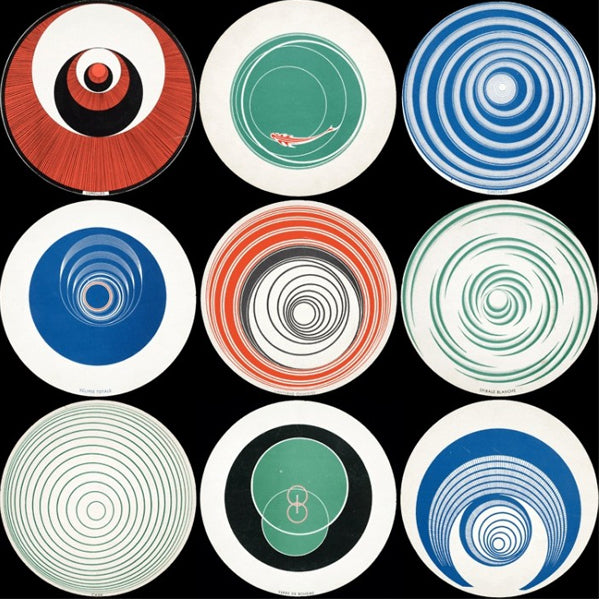

Marcel Duchamp, Rotoreliefs -1935.When spun on a turntable at 40–60 rpm these double sided discs create an optical illusion, a manifestation of Duchamp’s interest in mechanical art. Duchamp and Man Ray filmed early versions of the spinning discs for the short film Anémic Cinéma

It must be admitted, though, that while Duchamp certainly did implement and utilise a diverse range of artistic materials and mediums, his output was actually quite limited. It is the artist’s fundamentally profound theories that account for his growing impact on countless waves of twentieth-century art movements. His seminal concept of the mass-produced readymade attracts Pop artists and Minimalists alike, whereas Fluxus, Arte Povera and Performance artists appreciate Conceptualism’s performative aspects. But, Duchamp shaped the tastes of Western art in a more direct way too, since he was known to advise modern art collectors, such as Peggy Guggenheim.

Marcel Duchamp, L.H.O.O.Q - 1919

The art world’s leading figures alive now, unsurprisingly, follow Duchamp’s beaten path. Richard Hamilton made the copie conforme of The Bride Stripped Bare that is on permanent view at Tate Modern; Damien Hirst’s spot paintings are made by a team of assistants, rarely him; Ai Weiwei and Jeff Koons – arguably the two most prominent artists in the world – are thought of as the modern standard bearers of Duchamp. Whereas, it only takes a glance towards the likes of the Turner Prize, Frieze Art Fair, or quite obviously, the Pompidou Centre’s Marcel Duchamp Prize, to know it is a tradition very much in full-flow today.

Left: Marcel Duchamp, 'Fountain,' 1917. Right: Jeff Koons, Balloon Dog (Red), 1994

Perhaps Duchamp foresaw this enduring influence when writing his own epitaph: "D'ailleurs, c'est toujours les autres qui meurent" ("Besides, it's always the others who die"), it said. His work lives on beyond the grave. But the risk, as Duchamp admitted, is the ease with which art can now be made, without serious thought or care. “I know there is an inherent danger in the ready-made, and that is the ease with which it can be produced,” he said in an interview with Belgian television in 1966. “If you were to create tens of thousands of ready-mades per year, it would become extremely monotonous and irritating. These people die and the work dies with them. And that is where the history of art begins."