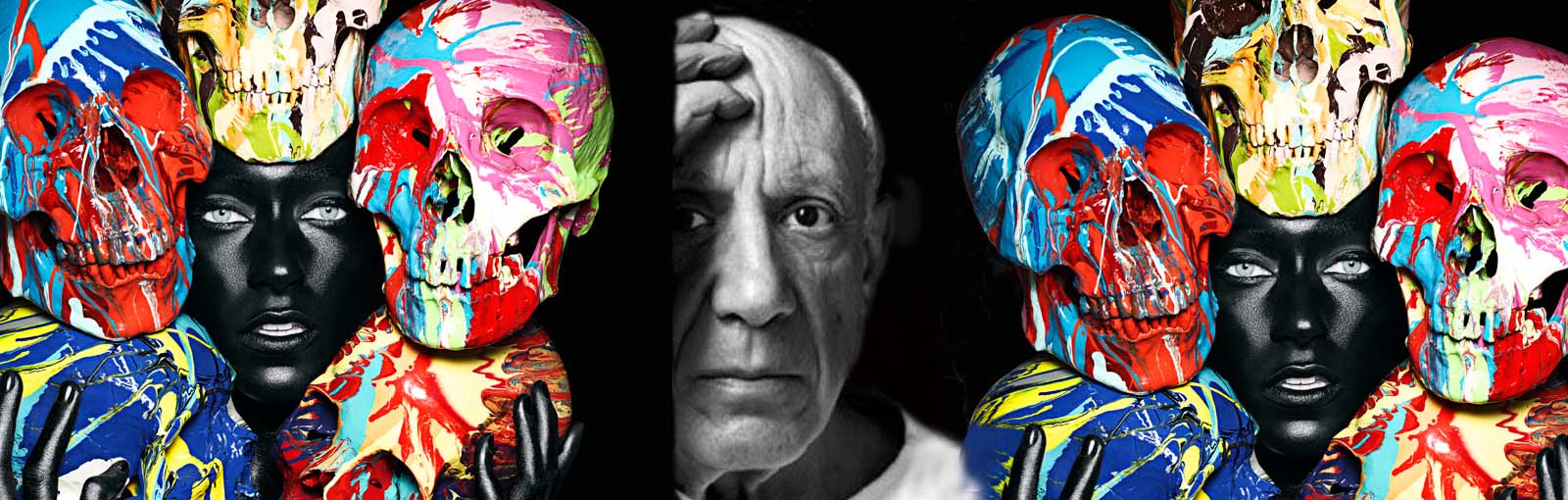

WHY THERE WILL NEVER BE ANOTHER PABLO PICASSO

How the art-world is killing innovation

by Peter Yeung

In an age where a hyped profile, gallery representation, and a need to follow the zeitgeist is key, the likelihood is that there will never be another Pablo Picasso. The great innovator of 20th century art was an artistic chameleon who painted, sculpted, experimented with printmaking, learnt the skills of ceramics, innovated with stage design, as well as dabbling in poetry and playwriting. Throughout time he mutated and morphed his style and philosophy from the austere gloom of his Blue Period, to the warm and optimism of the Rose Period, the startling imagery of his African-influenced period, and of course, his late experimentations with Cubism. But if he were alive today, Picasso’s press release would be cut in half so that a clean-cut image and narrative could be created.

Young assistants at work in Kai Kiki Co., Takashi Murakami's studio factory. His paintings have sold at Sotheby for a record of $4.2 million, in 2012.

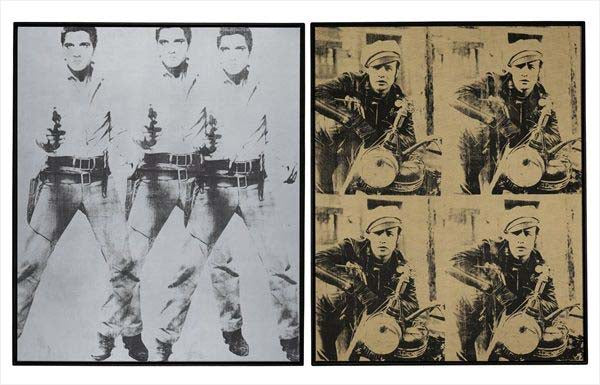

Don’t be fooled by the money. Even though the art world is in recession-defying rude health – Christie’s recently took a record $853 million in a single auction, itself breaking its own record of $745 million from six months before – it is dangerous to equate outrageous financial success with widespread health and stability. It speaks volumes that Christie’s age-old rival auction house Sotheby’s collection of $350 million was considered practically a measly figure. Meanwhile, in London last year, the most lucrative ever auction of impressionist and modern art took place, gathering £412m in sales (a 33.6% increase on 2013) and exceeding any sale in that category for almost a decade.

Andy Warhol portraits, "Triple Elvis,"1963 left, and "Four Marlons". These two iconic Warhol paintings sold for more than $151 million at Christie, breaking action records.

It’s pure irony that the late Picasso’s art works are now rocketing in value, when he’d never survive in today’s climate. Millions of dollars are spent by Chinese art collectors on Pablo Picasso's in vogue paintings, as the purchasing power of the BRIC countries inflates the value of the past masters. New money is looking to show off its strength, and invest in authenticity. Whole “villages” in China are well-oiled machines dedicated to replicating classic paintings, with hundreds of painters tasked with churning out dozens of copies of Van Gogh’s The Sunflowers, Money’s Starry Night et al. It’s surely time to despair when celebrities such as Kanye West are claiming to be the new version of the great Spanish artist. There’s no space for 21st century creativity.

Jeff Koons on the the cover of 'New York' magazine, May 13 2013

The reality is that the art market is becoming perilously top-heavy. The artist-as-personality – no matter how brash and uninspiring they may sometimes be – is floating to the top, funded by blue-chip billionaires and oligarchs, while those who fail to conform to modern sales standards sink. Jeff Koons, Marina Abramović, Damien Hirst, and even the likes of actor Shia Labeouf have been valued because of their capacity to go viral, with their scandalous, tabloid-baiting works. Look at us doing nothing, while earning millions for calling it art, they must wonder, while they wholeheartedly give pseudo-intellectual explanations. Why critically assess your own work if it sells so well?

The truth is that certain artists, backed by a battalion of publicity managers and image strategists, will always do well. Much in the same way that the Harvey Weinstein’s Hollywood dynasty dominates, or even the supposed invincibility of global banks, they are simply too big to fail when their funding and exposure eclipses the majority who struggle to survive. Necessary narratives are constructed on a cyclical basis to fit with the faster pace of the art market and the prospering art fairs that dictate it. This is rarely the natural work process of an artist, however, and this imperative to produce on deadline means that creativity suffers.

. Actor Shia Labeouf

Actor Shia Labeouf

In this increasingly privatised art world, it is harder for artists to find the freedom to experiment. Investment into grassroots and emerging artists is all but nonexistent. The UK Arts Index shows that in 2009/10, each person in the UK received around £19.64 in terms of public funding for the arts. By 2011/12, that had dropped to £16.42, and has continued to so. On top of this, studio prices are becoming unaffordable, while volunteering in the arts has been forced to increase by around a quarter of a million people since 2007. For genuine creativity to thrive, governments and societies need more foresight. Those that dare to be different need to be given funding, and a platform – Pablo Ruiz y Picasso didn’t need those aids, because it was a different planet when he was born in 1881. Otherwise, the art world’s thin, flimsy exterior will continue to burn brightly, but its insides will rot.